A “parlour council house” in the UK, built between the two World Wars, is special because of its parlour—a fancy room for special occasions. These houses usually have two or three bedrooms, a kitchen, and a bathroom.

Moreover, they’re better than the old slum houses, with strong walls and big rooms. Parlour houses came after the wars to give working families better homes. Now, people don’t use the parlour much, and some houses have changed, but they’re still important in British history, showing how folks wanted better homes in the early 1900s.

History of Parlour Council Houses

Emergence (1919-1923):

During the aftermath of World War I, the United Kingdom faced a severe housing crisis characterized by dilapidated living conditions and overcrowded slums. This predicament prompted governmental intervention through the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1909 and the Addison Act of 1919.

Further, the latter aimed to address the crisis by initiating a construction boom known as “Homes fit for Heroes.” This initiative focused on building well-constructed and spacious residences for returning soldiers and working-class families.

One notable architectural development during this period was the rise of Parlour Council Houses. These houses were designed with careful consideration for the needs and aspirations of the residents.

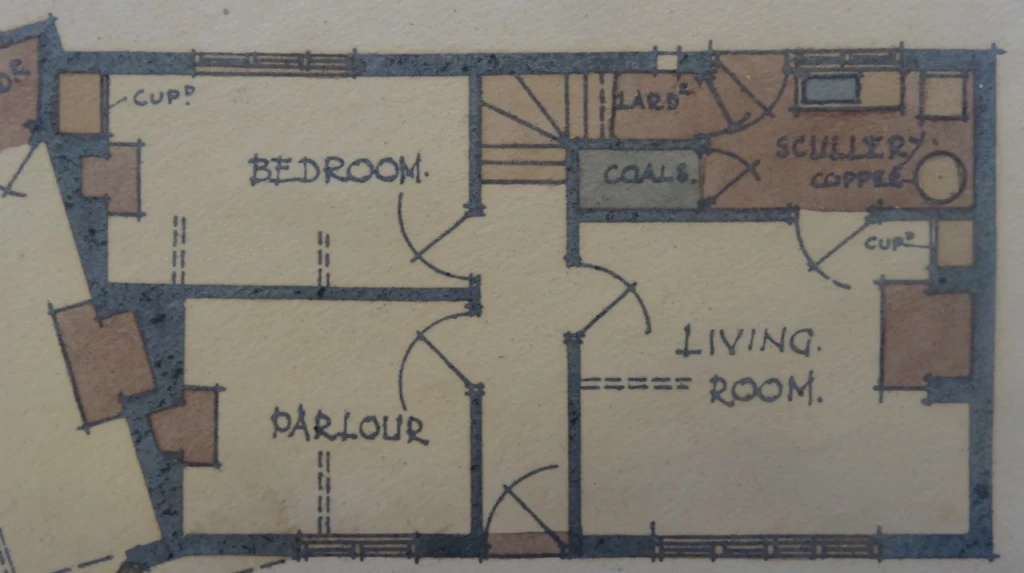

So, typically featuring 2-3 bedrooms along with a separate parlour, scullery (utility room), and bathroom, they provided a significant improvement over the cramped conditions of the slums. The inclusion of small front and back gardens encouraged self-sufficiency among residents. Constructed with solid brick or stone, these houses exemplified durability and longevity.

Lastly, the distinctive feature of the parlour within these council houses reflected Victorian and Edwardian ideals of respectability and social status. It served as a space for receiving guests and displaying the best furniture, adding an element of prestige to the living quarters.

Evolution and Decline (1924-1940s):

The momentum of constructing Parlour Council Houses faced challenges with the Chamberlain Act of 1923, which reduced government subsidies, slowing down their construction. Budget constraints shifted the focus towards smaller and more cost-effective housing options. This shift saw the rise in popularity of alternative housing types such as bungalows and flats.

Legacy and Significance:

Parlour Council Houses played a crucial role in elevating living standards for many working-class families. These residences offered a marked improvement in terms of privacy, space, and amenities like indoor plumbing, contributing significantly to the well-being of their inhabitants. Council estates, comprising Parlour Council Houses, fostered a strong sense of community, creating lasting social bonds among residents.

Further, some of these houses are now recognized for their architectural heritage and cultural significance, standing as a testament to the era’s design ethos and societal aspirations.

Criticism:

Despite their positive impact, Parlour Council Houses were not without criticism. Overcrowding, the lack of amenities like central heating, and limited maintenance posed challenges for some residents. These issues underscore the complexity of addressing housing needs while navigating evolving societal and economic landscapes.

Features of Parlour Council Houses

Parlour council houses, constructed predominantly between the two World Wars, epitomized a transformative shift in living standards for working-class families. Noteworthy features of these residences include:

The Parlour:

Function: The parlour served as a formal space, symbolizing respectability and social standing. Initially used for hosting guests during special occasions, displaying prized furniture, and providing a quiet retreat for reading or music.

Evolution: In contemporary settings, the parlour has often been repurposed as a dining room, secondary living space, or a home office.

Other Distinctive Features:

Bedrooms: Typically comprised 2-3 bedrooms, though larger designs were not uncommon.

Scullery: An independent room dedicated to cooking and washing up, strategically separated from the main living areas to contain mess and odors.

Small Gardens: Both front and back gardens were integral, promoting self-sufficiency and offering outdoor spaces for recreation and socializing.

Solid Construction: Employing durable materials like brick or stone, these houses were built with longevity in mind.

Additional Amenities: While central heating was not universally present, many featured indoor plumbing, a significant advancement from previous tenement living conditions.

Layout and Design:

Typical Layout: A common arrangement included a living room, parlour, kitchen/scullery, downstairs bathroom, and upstairs bedrooms.

Variations: Regional differences led to diverse features such as bay windows, fireplaces, or larger gardens.

Modernizations: Over the years, numerous houses underwent renovations and extensions to accommodate evolving needs and preferences.

Beyond the Physical:

Community: The construction of council estates with parlour council houses fostered robust community bonds, promoting a sense of belonging.

Representation: These houses symbolized a substantial enhancement in living standards for working-class families, offering unprecedented privacy, space, and comfort.

Challenges: Challenges, including overcrowding, occasional lack of central heating, and limited maintenance, were experienced by some residents.

Parlour council houses stand as a captivating testament to early 20th-century housing reform and evolving social aspirations. Their enduring presence and adaptability continue to stimulate discussions regarding affordable housing and architectural heritage.

Significance of Parlour Council Houses

The significance of parlour council houses extends beyond mere shelter, encompassing profound impacts on social, cultural, and historical dimensions. Here is an in-depth exploration of their influence:

Improved Living Standards:

- A Departure from Slums: Parlour council houses marked a stark improvement for working-class families, offering respite from the overcrowded and dilapidated conditions of tenements.

- Privacy and Dignity: Providing two to three bedrooms, a dedicated parlour, and separate living spaces represented a luxurious departure for many, promoting dignity and fostering family life.

- Modern Amenities: The inclusion of indoor plumbing, electricity, and small gardens contributed to enhanced sanitation, improved health, and an overall elevated quality of life.

Community Formation:

- Council Estates: Clusters of parlour council houses facilitated the development of tight-knit communities, fostering a profound sense of belonging among residents.

- Shared Spaces: Green areas, playgrounds, and community centers provided venues for socialization and connection.

- Resilience and Identity: The shared experiences of residing in these houses forged a unique collective identity within communities.

Architectural and Cultural Value:

- Reflecting Social Aspirations: The parlour itself embodied Victorian and Edwardian ideals of respectability and social mobility, serving as a visible marker of improved social status.

- Vernacular Architecture: These houses represent a distinctive style of interwar council housing, with regional variations enhancing their cultural significance.

- Preservation and Heritage: Recognized as heritage sites, some parlour council houses serve as tangible links to past social history.

Ongoing Relevance:

- Affordable Housing Debates: Parlour council houses underscore the ongoing need for decent, affordable housing for all.

- Urban Planning and Renewal: The study of their layout and community aspects informs contemporary approaches to building inclusive and sustainable communities.

- Social History: These houses act as invaluable time capsules, offering insights into the lives, aspirations, and challenges of the working class in the early 20th century.

Furthermore:

- Ongoing Debates: Discussions persist, with some highlighting challenges like potential overcrowding and the lack of modern amenities in parlour council houses.

- Adaptability: Their ability to be modified and seamlessly integrated into contemporary life underscores their enduring relevance.

FAQ’s

What is the meaning of Councillor house?

A council house is a dwelling owned by a local council, available for low-cost rent. In American English, it is synonymous with government-subsidized housing.

What does council house mean in the UK?

Historically, council housing in the UK refers to publicly owned housing rented to households unable to afford private sector rent or home ownership. It is managed by district and borough councils.

What is a British council house?

A council house (or council flat) is a type of British public housing built by local authorities. Council estates are complexes containing multiple council houses and amenities like schools and shops.

How much is council house rent in the UK?

The rent for council houses in the UK is subject to change, but as of December 14, 2022, there was an average increase in social housing rent and affordable rent, ranging from £4.71 to £7.58 per week.

Who is called councillor?

A councillor is a member of a local council, contributing to local governance and decision-making.

Final Words:

In summary, a parlour council house is a distinct type of residence constructed by UK councils, notably during the interwar period (1918-1939). The defining feature is the parlour, a formal room for special occasions.

Further, these houses typically comprise two or three bedrooms, a kitchen with a scullery, and a separate bathroom. Built to higher standards than the previous slum housing, parlour council houses represent a significant improvement in living conditions for working-class families.

Although the use of parlours has declined and many houses have been modernized, these homes remain vital in British architectural and social history, reflecting aspirations for improved living standards in the early 20th century.